President Donald Trump’s plan to distribute a “$2,000 tariff dividend” has caught attention of the nation, it immediately became one of the most talked-about proposals in U.S. politics. MAGA supporters hailed it as a way to return “dollars from foreign countries back into US citizens pockets,” while critics dismissed it as fiscally irresponsible. But what are the finer details we know about this plan like Who is eligible, By when will the deposits happen etc are still yet to be clarified by Trump’s administration.

As details trickle out, one thing is clear: the $2,000 will not be unconditional. A series of eligibility thresholds, income limits, and structural caveats are already being discussed both inside and outside government circles. Below, we unpack what’s known—and what’s likely—about the conditions that may apply before any American sees that money.

1. Income Thresholds and “High-Income” Exclusions

Trump has said repeatedly that the dividend would go to “everyone except high-income people.” However, he has never defined what counts as “high income.”

Economists and policy insiders suggest that the administration may borrow from previous stimulus check frameworks. During the 2020 and 2021 COVID-era payments, individuals earning more than $75,000 ($150,000 for couples) saw their stimulus reduced or eliminated. A similar sliding scale could appear in the tariff dividend plan.

Several Treasury sources told ABC News and The Washington Post that early drafts of the idea included an income phase-out starting around $100,000 per person or $200,000 per couple. These thresholds would allow roughly 85 percent of taxpayers to qualify, while excluding the top income brackets Trump has called “globalist elites.”

However, because the dividend is theoretically funded through tariff revenue rather than new spending, some aides have floated even higher cut-offs to avoid excluding middle-class families who face increased import prices due to tariffs.

Likely condition: Americans with middle or lower incomes will qualify in full; those above a certain (still-undefined) income level will receive partial or no payments.

2. Citizenship and Residency Requirements

Like previous federal stimulus efforts, the tariff dividend would almost certainly be limited to U.S. citizens and legal permanent residents who file taxes or receive Social Security.

Non-resident aliens, undocumented workers, and temporary visa holders are not expected to qualify. There are also ongoing discussions about whether dependents—particularly children—would receive smaller payments (such as $500 or $1,000) as part of a household dividend.

To prevent fraud, the payments would likely be distributed via IRS tax records or direct deposit accounts already linked to federal benefits systems. Those who don’t file taxes might have to submit a simplified claim form, as was the case with previous economic impact payments.

Likely condition: Legal residency or citizenship, along with a valid Social Security or Tax ID number.

3. Income Reporting and Tax Filing Status

One major uncertainty concerns whether the “dividend” will be treated as taxable income or a tax-free rebate.

If it’s structured as a direct fiscal payment, like COVID-19 relief checks, it could be exempt from taxation. But if the government channels it through tax filings—such as a refundable tax credit—it might reduce future tax bills rather than arrive as cash in the mail.

That means Americans who haven’t filed taxes recently or who are behind on returns could risk missing out unless they update their filings. Treasury insiders say the IRS will likely use 2024 tax data to determine eligibility, meaning your 2024 filing status could directly affect whether you receive the money in 2026.

Likely condition: Must have filed a federal tax return (or claim form) for the most recent year available.

4. Exclusions for the Wealthiest Households

Several reports—most notably from Business Insider and The Los Angeles Times—indicate that Trump’s economic team is considering a top-bracket exclusion. Under this model, households earning over $400,000 a year (roughly aligning with President Biden’s previous tax thresholds) would be fully excluded from receiving payments.

This would help frame the dividend as “a middle-class refund,” politically resonant for Trump’s populist base, while avoiding accusations that the plan rewards the ultra-rich.

Likely condition: No payments for the top 5–10 percent of earners.

5. Tariff Revenue Dependency

Perhaps the biggest hidden condition is whether there’s enough tariff money to fund the plan at all.

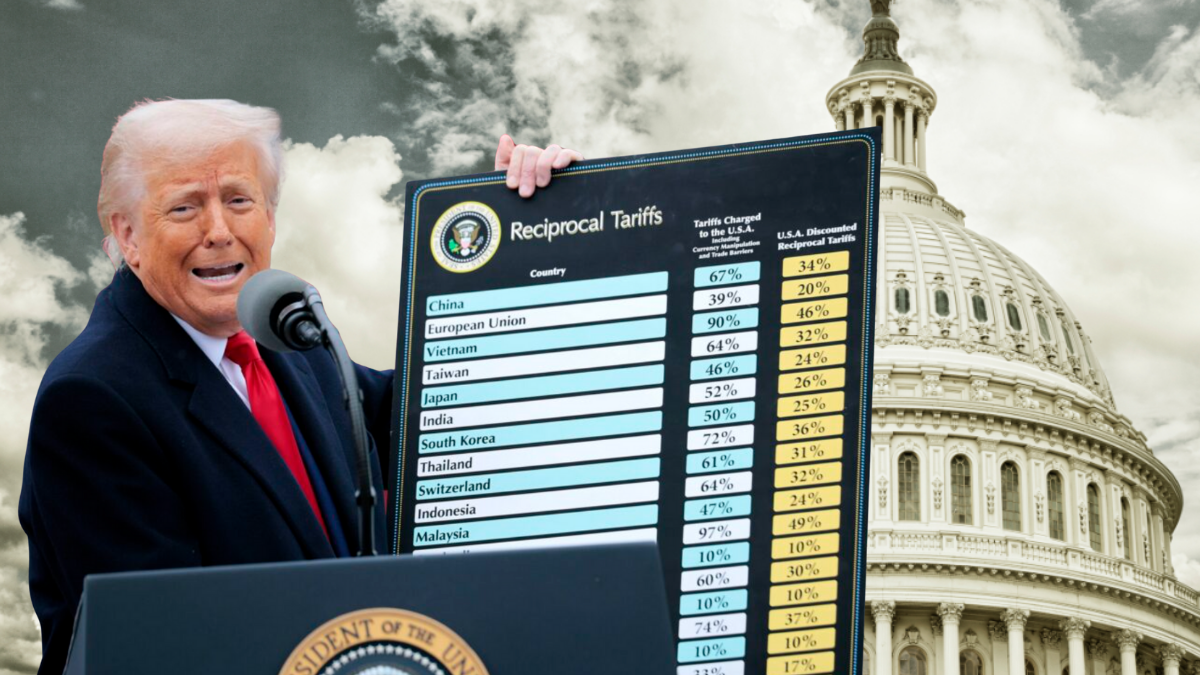

Trump’s tariff proposals target imports from China, Mexico, and the European Union, among others, and could generate between $250 billion and $350 billion annually, according to optimistic White House projections. But independent analysts warn that those figures may be overstated.

If tariff revenues fall short, the payments could be smaller, delayed, or replaced by tax credits. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent acknowledged this uncertainty, saying the dividend might take “different forms depending on economic conditions.”

In essence, the payment depends on how much money tariffs bring in—and whether those tariffs survive legal scrutiny.

Likely condition: Dividend amount and timing depend entirely on actual tariff revenue collected.

6. Legal and Legislative Approval

At present, there is no enacted law authorizing the tariff dividend. For the payments to become real, Congress would need to approve an appropriation or revenue-distribution mechanism.

Alternatively, Trump could attempt to use executive authority under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) or other tariff laws to redirect tariff revenues directly to citizens. However, that approach would almost certainly face legal challenges.

If the Supreme Court rules against Trump’s tariff powers (as it is currently considering), the entire dividend structure could collapse. Thus, a key condition may be judicial survival: the plan can only proceed if Trump retains the authority to impose and collect broad tariffs.

Likely condition: The Supreme Court upholds Trump’s tariff authority or Congress passes enabling legislation.

7. Timing and Distribution

Early statements suggested that the dividend could be issued “within a year.” In reality, experts predict mid-2026 at the earliest.

Distribution could occur via:

- Direct deposit to IRS-linked bank accounts,

- Paper checks mailed through the Treasury, or

- Tax credit adjustments in 2026 returns.

If Congress ties the dividend to fiscal-year surpluses, payment timing could also vary by revenue quarter.

Likely condition: Payment timing contingent on 2026 revenue cycles and Treasury authorization.

8. Possible Reductions for Certain Debts or Obligations

Some analysts have speculated that the dividend may be offset for those with delinquent taxes, child-support arrears, or federal debts—mirroring how past stimulus payments were garnished.

That means Americans with outstanding obligations could see reduced or withheld amounts, even if they otherwise qualify.

Likely condition: No delinquent tax or federal debt arrears, or payment will be reduced accordingly.

9. Geographic or Sector Adjustments

A few political commentators have floated the idea of “regional bonuses” for states hardest hit by trade retaliation or manufacturing disruption. While unconfirmed, such an approach could reward swing states like Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania—echoing Trump’s focus on industrial recovery.

Alternatively, rural states with higher import costs might receive smaller dividends if consumer prices there rise faster than national averages.

Likely condition (speculative): Adjustments possible based on region or sectoral impact.

10. The Political Reality Check

Even if all of the above conditions are finalized, implementation will hinge on politics. The House and Senate would need to cooperate on distribution mechanics, and budget hawks—particularly within Trump’s own party—may resist turning tariff revenue into cash payments.

Meanwhile, international backlash could reshape the math: retaliatory tariffs could lower trade volumes and reduce revenue, indirectly shrinking the dividend pool.

Ultimately, the promise of a $2,000 check may play as much to political theater as to fiscal planning.

Conclusion

The idea of a $2,000 tariff dividend has captured public imagination, promising to “share the spoils of tariffs” with ordinary Americans. Yet beneath the slogan lies a web of conditions: income limits, citizenship rules, legal challenges, and economic dependencies that could shape—if not erase—the payment altogether.

If the plan survives legislative and judicial hurdles, the most likely recipients will be middle- and lower-income Americans, especially those who file taxes and maintain good standing with the IRS. For now, though, the dividend remains more concept than cash—a populist promise waiting for a legal and fiscal foundation.